Introduction

Squatting is the best way to increase strength and/or local endurance of your lower limbs. There are a variety of technical points to consider, but one of the most common mistakes and confusions is the foot positioning. Today I’ll talk about foot/toe position during the squat, what to do, what not to do, and why.

Toes forward claim

The squat (preferably with a barbell) is a highly functional movement because it’s transferable to many movements in sports and life, and it’s perfectly safe when performed correctly. Unfortunately, toe position during a squat causes a lot of confusion among personal trainers and physiotherapists, and it’s extremely common for health professionals to recommend a toes forward stance.

Forward toe positioning was also made popular and advocated by the infamous American physical therapist Kelly Starrett, which has only added to misinformation and confusion among athletes and the general population:

Let’s analyse this toes forward claim. In this video, Kelly Starrett says ‘we express external rotation torque by screwing the feet in, and knees out allows you to create more torque’. This doesn’t mean anything, but he is right in that keeping the toes in creates more torque in the knees, however the knee joint isn’t designed to bend with torque (which is dangerous). He then says, ‘somewhere between 5-12 degrees allows that hip to be optimally positioned’. Again, this is not based in any scientific evidence and it’s not clear what he’s referring to in terms of a hip being optimally positioned; what is optimally positioned, or optionally positioned for what exactly?

He then tries to ‘crank’ her hips in by pressing his hands into the sides of her knees, but he says she’s got nothing, meaning that when her feet are facing forward and her knees are out laterally past the outside edges of her feet, for some reason he can’t collapse her feet in, and doesn’t explain why he can’t do this. Then he gets her to turn her feet out 30 degrees and claims this ‘un-impinges the hip mechanically but with a loss of being in a stable position’. This again has no scientific consensus and raises some concerning questions: so is he saying the toes forward will impinge the hip but a 30 degree angle doesn’t? Why would you want to squat in an impinged position of the hip? Why is there a loss of a stable position by turning the toes out, as you’re squatting up against resistance not pushing knees out against resistance when squatting?

Internal rotation of the thigh

In this second video, he says that: ‘athletes turn their toes out, and what this typically means is that the athlete is missing internal rotation of that femur in flexion… and that if I’m missing relative internal rotation of my femur in flexion of the hip what ends up happening is I’m going to blow off that torque by turning the foot out that unloads the kind of the demands of the internal rotation and this is what the bottom of my squat looks like’.

This sentence doesn’t even make sense. Additionally, why does he want to create excessive internal rotation (turning in) of the hip while squatting, as this causes torsion of the knee joint because the ankle and foot are planted on the floor and cannot move, so excessive torque is created at the knee.

He goes on to say ‘so the demands of internal rotation are less on the femur because I’ve turned the foot out, but the problem is my knee is now in an unlocked position, and that’s where I tear my ACL and MCL’. Having an unlocked knee doesn’t cause ligament damage of the knee, especially not when squatting, and you need to unlock the knees to perform a squat anyway. He then claims he can fix things by working on internal rotation and flexion, but his stretch doesn’t involve hip flexion stretching but instead involves excessive internal rotation which is not needed in excess to perform a squat. He then says ‘at mobility WOD we try and make stretching and mobility a lot cooler’. He then puts his hip joint capsule under undue stress by forcing extreme internal rotation using a band and his skull kettlebell.

He says ‘many of you will feel a pinch’ when demonstrating extreme internal rotation against the wall, but this is normal when you’re forcing extreme ranges of motion with internal rotation of the hip because you’re trapping the joint capsule and risk tearing the cartilage, and so I would not recommend this. I strongly advise you don’t try these stretches as extreme internal rotation is unnecessary to squat with correct form, has no functional carry over, and his obsession with internal rotation of the hip when squatting is irrelevant, dangerous, and unnecessary.

I strongly advise that if you want to perform time-wasting stretches that are irrelevant to a movement, then generally stretch muscles, and I do not advise you to work on the mobility of joint ligaments, as this will lead to a lack of joint integrity. When you squat with feet forward in a loaded squat, you put undue torsional stress on a simple hinge joint such as the knee; the knee is not designed to twist, it is designed to predominately hinge in a straight line.

Anatomy never lies

From the diagram below you can see that the average amount you can internally rotate your hip (turning the thigh bone inwards) is normally 40 degrees and is limited by tension in the ischiofemoral ligament, posterior capsule and lateral rotator muscles (muscles that turn the thigh outwards). Therefore, it would be unnecessary and dangerous to try to force increased range of motion (ROM) because firstly it doesn’t inhibit the ability to perform a squat, and secondly it increases the chances of soft tissue injury.

If your toes face forward, you lengthen the gluteal muscles because you take the insertion of these muscles further away from their origin. It’s easy to understand that when a muscle is lengthened it’s at its weakest, and when it’s shortened it’s at its strongest. Therefore it makes sense to partially shorten the gluteal and pelvic muscles using a toes out position so these muscles can participate in extending the hips and/or abducting the hips so you can produce maximal force safely to stand back up in the squat.

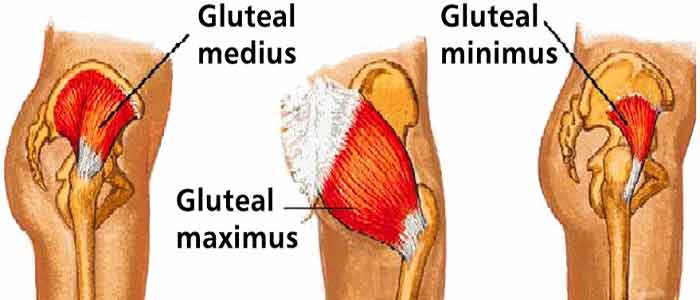

Let’s briefly look at the anatomy of the muscles that do this so we can see how they pull on the pelvis and greater trochanter (the big bony portion at the top of the femur bone which these muscles attach to):

In very basic terms (see foot note* for further details), your gluteus maximus (your biggest bum muscle) basically originates from your sacrum, and inserts onto the side of your hip bone, and it extends your hip, stabilises your hip and knee, and laterally rotates and abducts your thigh so it makes sense for it to work in its prime position during the squat which is with the toes positioned out. If the toes face forward, and acknowledging how and where the gluteus maximus inserts onto your thigh bone, you would be taking the origin away from the insertion and lengthening the muscle, putting it in an anatomically weak position to squat with. What about the rest of your hips muscles? Well, there’s another 7 muscles involved in rotating your thigh outwards so it would be in your best interests to use these muscles optimally in the squat by contracting them by using a toes out position.

What do EMG studies say?

Electromyography (EMG) is a diagnostic procedure to assess the health of muscles and the nerve cells that control them. Research has been conducted to measure muscle activation by EMG for the squat with a view to clarify how the exercise can be applied most effectively. Analysis of muscle activity has included the rectus femoris (one of the quadriceps thigh muscles) and hip adductors (adductor longus and gracilis, muscles in the inner thigh) during the squat with the hip in a neutral (0 degrees, i.e., toes facing forward) versus a rotated 30 or up to 60 degree position (i.e., toes facing outwards), in 3 stance width positions, with a 90 degree ROM (parallel squat).

It was found that muscle activity of the hip adductors and gluteus maximus (main bum muscle) were significantly greater with the hips rotated out, creating a toes out position. Therefore, as the purpose of the squat is to overload the primary movers, then the stance width and hip external rotation should be used to squat safely, to the appropriate depth, and to lift the largest amount of weight to get the largest amount of strength or endurance gains. Meanwhile, both studies found that the myoelectric activity of all muscles was amplified as ROM increased, so squat depth matters.

The results suggest that inner thigh activity is dependent on the degree of hip external rotation (maximum of 30 degrees of hip external rotation). In addition, adductor activation only varies with hip position within a limited ROM. The adductor magnus (inner thigh muscle) not only brings the leg towards the centre line of the body, but it also aids in hip extension, i.e., in this case helping with producing force to stand up from the bottom of the squat. When the hips are externally rotated, the adductor muscles are in a better position to help out.

Stance width

As a side note, stance width doesn’t affect muscle activation of the quadriceps contrary to popular belief. For example, studies show that stance width (hip width, shoulder width, and shoulder width and a half) don’t affect muscle activation but loading did as the closer one performs the squat to one repetition maximum (1RM). Rather, muscle recruitment during squats has been found to be more dependent on joint position, ROM, and effort level.

Do these 2 tests to prove increased range of motion with toes out?

To demonstrate increasing range of hip flexion, you can perform a simple test:

Lie on your back on the floor, pull one knee directly to the chest with the knee bent and make a note of the ROM. Now externally rotate the hip (i.e., turn your toes and thigh bone out in line with your arm pit), and you’ll find you can flex the hip further, and the same principle applies to the squat.

The reason this happens is because the thigh bone (with hip flexion with no external rotation) traps connective soft tissue at the hip, and also checks on the pelvis. Therefore, utilising the fullest hip ROM (that being external hip rotation with hip flexion) creates greater squat depth while maintaining proper pelvic positioning, and therefore proper lumbar spine extension. This is acquired with a toes out position.

Another simple test you can do is squat down as deep as you can go with the feet facing directly forward while standing on a shiny surface, preferably in your socks. You’ll probably find that the feet will want to naturally turn out as you squat deeper down to depth. You may also discover the toes forward position may encourage knees to cave in (medially, i.e., valgus), encouraging the hip to internally rotate, and may cause a sensation of the hip ‘pinching’.

What degree should your toes be turned out?

Your knee joint will be compromised if it twists as it flexes. So how does this affect your squat depth and foot width? Well, the deeper your hip and knee flexion, the less relevant the toe position, so in other words the more shallow your hip flexion (squat depth), the less concern of knee torque and valgus or varus (knees going in or out, respectively). However, there is little benefit to shallow squats as it doesn’t work all the musculature involved adequately enough, so we’re back to the point of toes out and a deeper squat.

In terms of foot width, the wider the stance the more you have to turn the toes out in order to keep the knees tracking in line with the toes and prevent your knees caving in. Now imagine this happening under a loaded bar; the risk of injury is of magnitude. According to the research, it would be best practice to turn the toes out approximately 30-40 degrees, and therefore the hip is also externally rotated 30-40 degrees with your heels being between just over hip width apart to shoulder width apart.

Additional reasons to turn your toes out

Firstly, a toes out angle of 30-40 degrees enables your thighs to get out of the way of the gut when squatting down, thus allowing a more comfortable exercise. This also works best for pregnant women, so that the legs aren’t folding onto the abdomen.

Secondly, externally rotating and abducting the thighs allows your glutes and the small gluteal muscles to maximally contract and aid in the force output of the squat (i.e., building a better bum.

The bottom line

Squatting with feet forward is biomechanically inefficient and dangerous. It will also limit your loading in the squat exercise, which will limit your overall strength and have a negative effect on maximising sporting performance. Lining up the entire lower limb with minimal knee torque maximises force production and joint mechanics, and your toes should be turned out about 30 degrees to prevent the knees twisting.

With the toes forward, you will have to force your knees outside of the direction of the feet and the tibia will internally rotate; this biomechanical disadvantage places excessive torque on the knees because the feet are firmly planted on the ground and therefore the tibia and ankle bone movement is compromised. The hips have the largest ROM in the lower limb and therefore it makes sense for the hips to be externally rotated in order to place less torque on the knee joint which has a more fixed plane of motion.

*Foot note:

Further anatomical details of hip musculature:

Gluteus maximus:

Origin:

- Fascia covering gluteus medius

- Gluteal surface of ilium behind posterior gluteal line

- Fascia of erector spinae

- Dorsal surface of lower sacrum

- Lateral margin of coccyx

- External surface of sacrotuberous ligament

Insertion:

- Posterior aspect of iliotibial tract of fascia lata

- Gluteal tuberosity of proximal femur

Action:

- Extends hip

- Through its insertion into iliotibial tract it also stabilises knee and hip joints

- Upper fibres laterally rotate and abduct

- Lower fibres adduct

Gluteus medius:

Origin:

- Gluteal surface of ilium between posterior and anterior gluteal lines

Insertion:

- Via a flat tendon on upper lateral aspect of greater trochanter

Action:

- Abducts femur

- Medially rotates thigh

This muscle attaches to the large bony portion of the femur (greater trochanter) and although it doesn’t help to extend the hips from the bottom of the squat, it helps to keep the knees in line with the toes because it abducts the femur.

Piriformis:

Origin:

- Anterolateral surface of sacrum between anterior sacral foramina

- Sacral segments 2-4

Insertion:

- Passes through greater sciatic foramen onto greater trochanter

Action:

- Laterally rotates femur

- Abducts flexed femur

Again the job of the piriformis is to laterally rotate and abduct the femur so it can participate in keeping the knees aligned with the toes out position. The same case can be made with the following muscles:

Quadratus femoris:

Origin:

- Ischial tuberosity just below acetabulum

Insertion:

- Quadrate tubercle on intertrochanteric crest

Action:

- Lateral rotation of the hip joint

- Abducts the flexed hip (horizontal extension)

Gemellus superior:

Origin:

- Gluteal surface of ischial spine

Insertion:

- Tendon of obturator internus

- And into medial side of greater trochanter of femur

Action:

- Lateral rotation of the hip joint

- Abducts the flexed hip (horizontal extension)

Gemellus inferior:

Origin:

- Upper part of ischial tuberosity

Insertion:

- Tendon of obturator internus

- And into medial side of greater trochanter

Action:

- Lateral rotation of the hip joint

- Abducts the flexed hip (horizontal extension)

Obturator internus:

Origin:

- Deep internal surface of obturator foramen and surrounding membrane and bone

Insertion:

- Medial side of greater trochanter

Action:

- Lateral rotation of the hip joint

- Abducts the flexed hip (horizontal extension)

Obturator externus:

Origin:

- External surface of the obturator foramen and membrane

Insertion:

- Trochanteric fossa of femur

Action:

- Lateral rotation of the hip joint

- Abducts the flexed hip (horizontal extension)

References

Clark, DR., Lambert, MI., and Hunter, AM. (2012) ‘Muscle activation in the loaded free barbell squat: a brief review’, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(4), pp. 1169-1178.

Drake, RL., Vogl, AW., and Mitchell, AWM. (2010) Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, USA: Churchill Livingstone.

Palastanga, N., and Soames, R. (2012). Anatomy and Human Movement. 6th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone.

Pareira, GR., Leporace, G., Chagas, DV., Furtado, LF., Praxedes, J., and Batista, LA. (2010) ‘Influence of hip external rotation on hip adductor and rectus femoris myoelectric activity during a dynamic parallel squat’, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), pp. 2749-2754.

Signorile, JF., Kwiatkowski, K., Caruso, JF., and Robertson, B. (1995) ‘Effect of foot position on the electromyographic activity of the superficial quadriceps muscles during the parallel squat and knee extension’, Journal of Strength and Cond Research, 9(3), pp. 182-187.